Heroes and Villains No 7 Ancel Keys (Part 1)

If you want to lose weight, it’s all about the CICO – Calories In Calories Out: or is it?

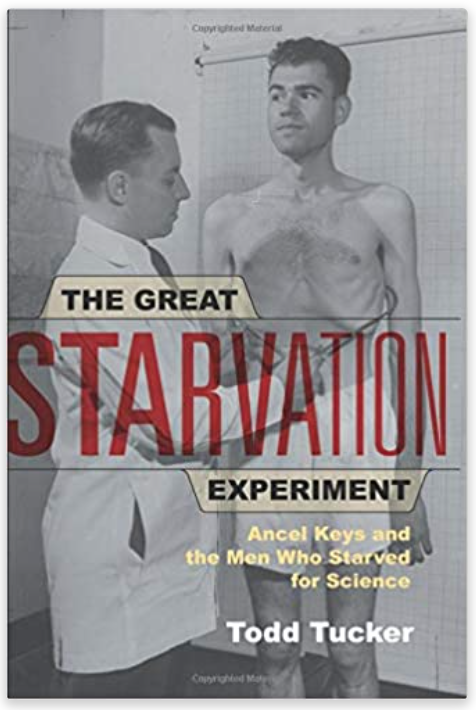

Calorie restriction is in practice an exceedingly difficult thing to do reliably. Controlling for all the various things that affect energy balance, for example, portion sizes, forgotten snacks and changes in exercise, even room temperature, is almost impossible to achieve. But one very determined group of researchers did manage to do a long-term test of Calorie restriction and pretty well ironed out the multitude of ‘confounding’ factors that often plague such studies. The study was conducted by scientists at The Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene based in the University of Minnesota, USA. They were led by a charismatic and exceptional scientist, Dr Ancel Keys. It was Keys and his team who conducted what later became known as The Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

Ancel Keys first came to public attention in the 1940s when he developed an innovative personal nutritional supply pack, for use in combat zones and known as K-rations. It is said that the K prefix referred to Ancel’s surname. K-rations provided a lightweight high-energy food supply that could nourish and sustain a soldier for up to two weeks in the field. Keys’ interest in nutrition grew, and during the 2nd World War he was recruited by the military to study the effects of starvation and re-feeding on human health and functioning.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment made Keys a household name. It was conducted with the encouragement of the US National Government. Its remit was to determine the effect starvation might have on populations, and to test out a variety of post-starvation rehabilitation regimes. In 1944 thirty-six young healthy white male volunteers were recruited from a register of conscientious objectors to military enlistment. The selection process was rigorous, only those identified as both physically and mentally fit, and deemed to have the right temperament to last the course, were selected. They agreed to live in a residential facility for almost one year during which time they were closely and intensively monitored. In fact, none of the 36 volunteers ultimately selected was literally starved. Instead after a baseline twelve-week observation phase during which they consumed around 3,200 calories a day, their daily food intake was halved to just under 1,600 calories and delivered across two meals a day. Throughout the starvation phase, regular periods of prolonged physical exercise were required. It was no coincidence that the recruits were all male and of military age and condition, and that the starvation diet mimicked potential European famine conditions soldiers might have to endure during deployment.

During the semi-starvation phase, which lasted for twenty-four weeks, the volunteers were frequently, regularly and intensively monitored for a number of physiological, psychological and behavioural variables. After this semi-starvation phase the volunteers were divided into several smaller groups and the effects of different calorie-level rehabilitation diets were tested for a further twelve-weeks. By the end of the forty-four weeks of observation, of calorie restriction and re-feeding, the volunteers were allowed to eat and drink what they wished. Some were monitored for a further couple of months.

The work Keys and his talented team put in was prodigious. The exhaustive report that followed, The Biology of Human Starvation, which ran to fifty chapters, in two volumes and almost 1,400 pages, was published in 1950. But what did the Minnesota Starvation Experiment reveal? What happened to these young healthy men?

Well, they did lose weight, quite a lot during the first 12 weeks of starvation, but less thereafter. By the end of the 24-week period of starvation volunteers had lost on average around 40 pounds (about 18Kg), representing on average almost one quarter of their body weight. Using the calorie- energy balance formula their weight loss should have been about double what was in fact observed. Before and after photographs reveal the changes as their physical conditions deteriorate from normality to emaciation. But this weight loss came at considerable personal psychological costs too. Their metabolic rates dropped in response to starvation, most became lethargic, their hair dropped out and their pulses slowed. Most spent as much time as they could inactive, lying down doing nothing. Their libido vanished. Almost all experienced intrusive and persistent obsessional thoughts about food and developed ritualistic behaviour at meal times. Food became the exclusive focus of their lives during this phase. For some, these behavioural adaptions became severe enough to be considered a mental illness. Indeed, one volunteer had to be removed from the study and transferred directly into a psychiatric institution. His condition rapidly and completely resolved when he was fed a normal diet. The lives of the volunteers were completely on hold during starvation, and this persisted well into the rehabilitation phase as well. By the end of the study, and after a time of free eating, all had regained weight. All consumed prodigious amounts of food each day for some time, and yet still complained of feeling hungry. Most ended up weighing more than they had before the trial.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment said a lot about famine endurance but nothing about healthy eating or about sensible ways to lose weight. Nor was the age, gender and ethnicity of the volunteers (which mimicked those of the US troops then fighting across northern Europe) typical of the population in general. The Starvation Experiment probably said more about the dedication, focus and tenacity of Keys and his team than anything else. But by the time the study concluded the outcome of the war had become clear. The prospect of starving GIs had regressed and the military’s interest waned.

But the Starvation Experiment told us something else as well. It illustrated what we all intuitively know anyway, and that is that our bodies are exceedingly complex. They adapt to changes in the environment including food supply. One biological response shown by all the volunteers was the significant slowing down of the body’s processes metabolism in response to calorie restriction. Their biology adapted to a low-cal diet by conserving energy, shutting down metabolism activity and focussing the mind almost exclusively on the getting and enjoying of food. Of course, they lost weight, they were being starved! But their weight loss did not follow the simplistic application of The Laws of Thermodynamic. It was not arithmetic as energy balance formulae and CICO would have us believe. This is because the volunteers, like us, were neither ‘closed systems’ nor ‘in equilibrium’. And, if extreme and prolonged starvation failed to evoke the weight loss predicted is it a surprise that modest caloric restriction rarely does precisely what Official Dietary Advice says it should either?

Ancel Keys was a colossal figure in story of nutrition in the 20th century and merits more than one entry into the pantheon section of the blog.. Next time we will look at his game changing studies in the 1950s and 60s and his demon baby – The Diet-Heart Hypothesis.